‘A New Politics of Solidarity’ (pre-print, December 2019)

What does it mean to describe the uprising of solidarity that spread across Europe in 2015, producing a surge in refugee-directed initiatives, as ‘political’? This question points us back to the tag ‘activist’ adjoined to the more readily used title of ‘volunteer.’ What does this adjective presuppose? And how does it translate across different dimensions of this mobilisation?

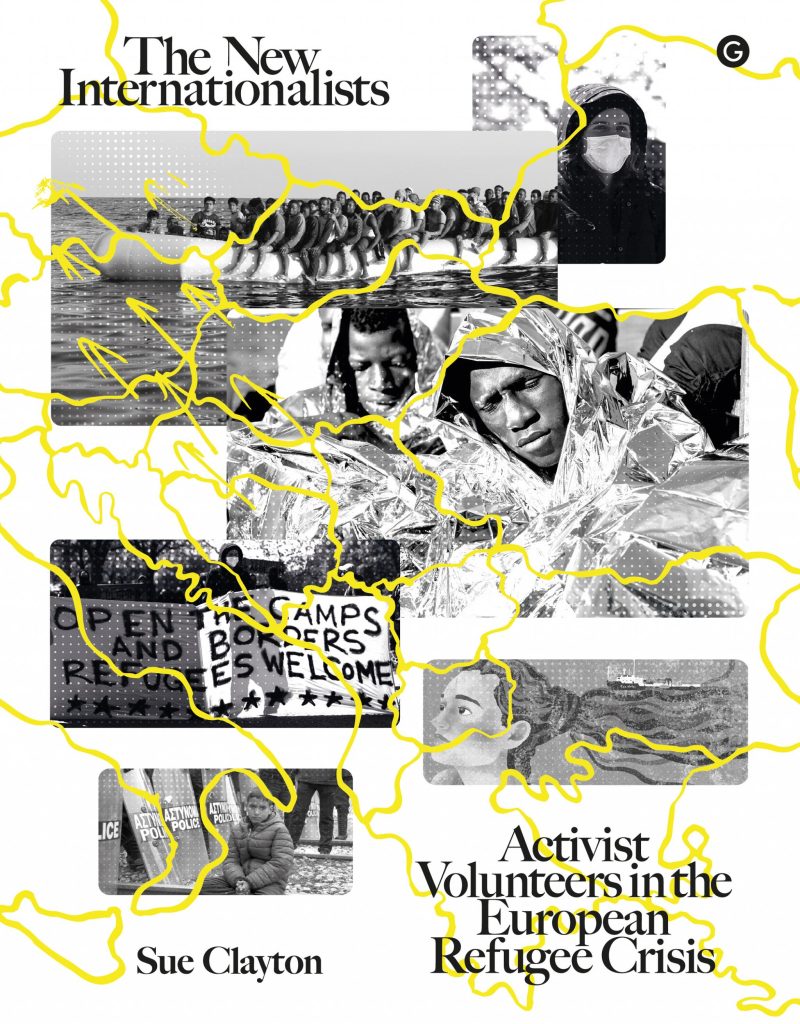

This chapter will plot a few key scenes (Athens, Paris, Rome, Calais) while touching more briefly on others (Riace, la Roya/ Ventimiglia, Brussels, Glasgow) in which the politicising of welcome has changed the stakes of the movement. It will look at how volunteers have developed creative strategies of opposition, and how these have established a continental frame for activism at a time when the transnational project of the European Union is under pressure from rising nationalist movements and the impact of austerity politics. What sort of divergencies and commonalities can be observed across the continent? How have the ‘new Internationalists’ intersected with deeply embedded structures of radical politics, conditioned in some countries by decades of struggle on behalf of migrant workers? And how are the new challenges of ever greater human mobility, particularly from the sites of conflict in the Middle East and East and Central Africa, changing the forms of political militancy within Europe across very different national political histories? This chapter will introduce readers to these questions and offer concrete examples of what we can perhaps discern as the new politics of solidarity in Europe in order to understand how they are attempting to shape the future.

In April 2018, leading a street demonstration in Paris against the Bill presented by Emmanuel Macron’s government to strengthen France’s legal arsenal for ‘combatting’ the so-called migrant crisis, the BAAM organisation celebrated the way students and the railway workers’ union had rallied to their protest. LGBTI flags and signs denouncing ‘Dublin’[1] waved over the demonstrators as they danced to Amel Bent ‘s song ‘Ma Philosophie’ with its lyrics of resistance – “Toujours le poing levé” (Always fist held high) – and shouts of “We are all the children of immigrants.” “This is the ‘social project’ for the future” declared one of the BAAM activists, co-opting and redirecting Macron’s term of a ‘projet social’ from a lorry above the crowd. “It’s happening here, in the street, in the fight for social rights, for migrant rights, for LGBTI rights… and not in the Senate, not in the National Assembly…”

BAAM stands for Bureau d’Accueil et d’Accompagnement des Migrant.es or the Office for the Welcome and Accompaniment of Migrants, but there is nothing ‘official’ about it. Launched in November 2015 after one of the main squats in Paris, located in the disused Jean Quarré high school and occupied by over 900 asylum-seekers from Afghanistan, Iran, Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia and elsewhere, was evacuated by the police, it has grown into a key locus of activism and support in Northern Europe. The squat was initially opened by migrants themselves.[2] Its visibility in a central Parisian district and its relative stability made it a focal point for people across the city and further afield, to get involved. Lawyers, students, teachers, social workers, journalists, job-seekers, pensioners as well as lots of people who have themselves negotiated the asylum system in Europe joined forces under its auspices, sometimes living on site until it was evacuated and had to seek other provisional premises, to provide language classes, legal advice and orientation, to accompany people to hospitals, to point them towards places to find food and shelter, and also to help them find work. Its work is ‘humanitarian’ in this sense, but it is also ‘political.’ It is anchored in the energy and commitment of highly skilled and often politicised local people, yet from its inception it was piloted equally by migrants who were also, though often differently, highly skilled and politicised. Volunteers from all over the world have contributed to its activities. It is explicit in the expression of its political demands, notably through a manifesto as well as street demonstrations, and it also functions mainly by donations and uses informal spaces (including outdoor spaces) for its activities. So it has remained resolutely independent of major NGOs, though it locates some of its classes in public libraries and thus depends, if indirectly, on municipal services. How can an example like BAAM, with these different facets rapidly summarised here, help direct our discussion of the changing shape of politics and conceptions of citizenship, and who we might consider to be ‘political’ in the mobilisationsgenerated in solidarity with refugee struggles most directly in Europe but also against the background of a new planetary consciousness? (McNevin, 2007; Elias and Moraru, 2015)

We will start by considering how a support network such as BAAM and others like it across Europe relate to and potentially develop recognisably political forms of activism. The latter include occupations, demonstrations, solidarity with established political organisations, including parties and unions, and even strikes. Are these tools of what we might call traditional political activism part of the mobilisation that this book describes and what connections do they thereby create with other contemporary battlefields?

We also have to think about what the roles of different people across the spectrum of the ‘refugee crisis’ are within these forms of activism. Many observers have strenuously criticised the traditional humanitarian sector for its tendency to limit the capacities for self-determination amongst people whose presence in Europe is very often the result of an uncompromising bid to take control of their conditions of life, defining this ‘crisis’ as one of ‘hospitality’ and not of ‘refugees’ (Agier 2011; Fassin, 2011; Holzer and Warren, 2015; Malkki 2015). BAAM grew out of a refugee-centred mobilisation and its politics are anchored in efforts to enable people without any access to mainstream forms of political representation to continue to fight in their own names. The second part of this chapter will focus on what it has meant within the volunteer-activist movement to enable this sort of ‘unauthorised’ or ‘non-citizen’ agency to emerge, and how that has conditioned the places and forms of activism for citizens of European states.

One of the consequences of working with people forced into situations of illegality and administrative precarity has also been the increasing number of ways in which European citizens have found themselves criminalised, whether intentionally or not, for a range of actions that go from ensuring basic assistance to people forced into the streets to accepting ‘irregular’ people into homes to assisting border crossing, preventing planes from taking off or bringing a ship into port (Fekete, 2018). This is another key facet of the changing shape of refuge-related activism, and one that has received widespread coverage in the press across Europe. How has the changing arsenal of laws and their application by the authorities shaped the work and words of volunteer-activism? How is the ‘extra-legality’ of some of this activism also changing what it means to be political or do politics today? And how does this dimension intersect with the often quite ‘domestic’ frame within which the actions are carried out? These questions will form the final part of this chapter, but they also need to be placed within the longer trajectory of political activism and compared to the way in which unlawful activities conditioned other key resistant movements through the twentieth century, from the French Resistance during the Second World War to the Black Panthers in the US. In this respect, we also come full circle to assess what some of these new internationalists owe to a lineage of radicalism.

Our exploration will take us from central squares and buildings in cities across Europe to small villages, ports, disused industrial sites and scrub land. Its time frame is loosely from Mayor of Palermo, Leoluca Orlando’s landmark decision in March 2015 to found the Charter of Palermo that enshrines the right to human mobility, to the summer of 2019 when national Italian politics shuddered and regrouped under a new coalition in part under the effects of the increasingly repressive response, spearheaded by extreme-right leader Matteo Salvini, to unassisted migrants arriving on the Italian coast. Between these dates and reaching back and outwards to other forms of protest, we will chart some of the ways in which activist volunteers have shaped the movement beyond a response to a crisis towards a radical recasting of international citizenship today.

Occupations

In August 2019, heavily armed Greek police marched into the self-governing community of Exárcheia in central Athens, targeting squats that have been home to autonomous groups of migrants and volunteers since the autumn of 2015, when at the height of the crisis in the Mediterranean steadily increasing numbers of asylumseekers found themselves sleeping in their hundreds on the streets of the city. As the police filed past the mosaics of protest graffiti and community posters, the inhabitants of this traditional student area were gathered around their street-based ‘Resistance Breakfast,’ showing a combination of determination to hold their ground and a commitment to feeding those in need. The decision to break the network of squats and anarchist groups that has grown over the years to make Exárcheia a hub of radical thinking and alternative living follows the election of a new government in July 2019 committed to restoring ‘law and order.’ By the time the police left on 26 August, four major squats – Spirou Trikoupi 17, Transito, Rosa de Fon and Gare -had been evicted, but the oldest and most symbolic squat amongst those initiated with and by migrants, Notara 26, was exempted in what observers judged was a reflection of the solidity of its organisation and protection. How does this recent history of Exárcheia fit within the broader sequence of ‘the hospitality crisis’ and the rise of increasingly authoritarian governments across Europe?

Surrounded by university buildings, including the Polytechnic School that was the bastion of opposition to the military regime of the early 1970s, this district of Athens has always been a space of resistance, cosmopolitan encounter and countercultural living, but the current concentration of anti-authoritarian action and its very direct engagement with the situation of people seeking safe haven and a future in Europe draws its uncompromising radicalism from events in December 2008, when the country was reeling under the effects of financial crisis. During a night of riots in Exárcheia 15-yr-old Alexis Grigoropoulos died under police fire. The outpourings of anger spread across the country before channelling the outrage into numerous anarchist and oppositional formations, many of which laid the groundwork for the subsequent victory of the Syriza movement. One such group was the Alpha Kappa which was instrumental in creating the Micropolis model of free social centres built around the solidarity or participatory economies, the development of small enterprises, the pooling of care and support through education, childcare and cooking. These experiments in new forms of sustainability, with their strong anchoring in ecological thinking, formed the laboratory for actions that gained new urgency as refugees found themselves stranded in Greece, particularly after the EU-Turkey agreement in March 2016 which set out a framework for the forcible return of ‘irregular migrants’ on Greek territory to Turkey, a framework vigorously denounced by NGOs and activists and ultimately also by the Greek asylum appeals committee. It was against this background of EU policy, which confirmed the prevailing high-handed and technocratic approach adopted by European states and institutions, that people from groups such as Alpha Kappa contributed significantly to the opening of squats for refugees, including Notara 26, and later the City Plaza Hotel outside Exárcheia, which survived from April 2016 until May 2017 when the hotel’s owner presented the local authorities with a massive bill for usage of the building in an attempt to force their hand by treating the population of East-Africans, Syrian, Afghanis and others, along with local activist volunteers, living in the ‘hotel’ as regular paying guests.

Though the political inflection of these squats varies, what they share and shared is a determination to offer an autonomous alternative to the centres and camps funded by the UNHCR in particular, through unauthorised occupation of empty city-centre premises. In their emergence they drew on a rich tradition of anarchist struggle, revitalised by the effects of the financial crisis and the endemic corruption of Greek political institutions. And this historic underpinning had important effects on the way these autonomous spaces subsequently evolved, particularly in the commitment to direct democracy and collective decision-making, as this chapter will go on to discuss (Brugère and Le Blanc, 2017). In turn, the challenges generated by the situation of those who found refuge in these alternative spaces are reshaping the landscape of political opposition in Greece, bringing a discourse of international solidarity to the fore in the demands for a new politics.

The transnational character of these occupations functions in multiple dimensions. Within these sites interactions take place across considerable linguistic differences. Residents communicate in combinations not only of Greek, English, Pashto, Arabic and Farsi, but also French, Spanish and Italian. Food has to be negotiated across a huge range of preferences and prepared collectively with limited resources. Rosters and responsibilities have to be shared out despite radically different priorities in individual trajectories. These necessarily very inward-looking and self-protecting spaces are also key hubs on a transcontinental map of solidarity, both for people pursuing their attempt to obtain asylum elsewhere in Europe and for activist volunteers concerned to channel their efforts towards places of greatest need. So when the Notara 26 squat was the target of a racist fire-bomb and Molotov cocktails in August 2016, resulting in the destruction of all of their supplies, 24 vans set off from across Europe, uniting in a convoy of solidarity from France, Spain, Belgium and Switzerland. Most of the squats with refugee residents also include European residents from countries further North and the walls of Exárcheia are papered with expressions of resistance and anti-authoritarianism in English, Arabic, French, Pashto as well as, of course, Greek, while a banner over the door at Notara 26 merely announces REFUGEES WELCOME and HOME, declaring in so doing that the discourse of occupation and opposition in Greece today is also a categorical affirmation of the possibility of offering shelter. One of the most frequent slogans heard in demonstrations against the repression in Athens is ‘Solidarity is the arm of the people’ as can be heard and seen in Yann Youlountas’s 2018 L’Amour et la révolution, made in support of self-governing spaces in Athens, which features scenes in Notara 26. ‘Solidarity does not only bring help and support. It also allows us to see the society we want,’ declares one of the cartels. For these activist-volunteers their politics are inseparable from their capacity to offer care.

The same observation can be made of similar forms of unauthorised occupation in other cities across Europe. Rome’s Baobab Experience, a huge camp installation established in an abandoned lot near the Tiburtina station in 2015, is another well-documented example of a combined volunteer-refugee-led mobilisation, where the effort has been to produce a stable environment of care and counsel, as well as to meet the immediate needs of food and shelter (Paynter, 2018). Baobab Experience thus extended its work from a ‘humanitarian’ response towards initiatives to change the discourse in Italy, to explore interconnected factors evident in the failure of European institutions to provide for the rise in asylum seekers entering Europe, and to offer a locus for resistance to the growing extremist tendencies within Italian politics. Like the squats in Exárcheia, Baobab’s momentum was crushed by Salvini’s rise to power as Minister for the Interior when he ordered its destruction and the eviction of those living there into the streets in November 2018.

Jean Quarré in Paris, Notara 26 in Athens and Baobab in Rome share high visibility largely because of their size, their relative organisation and stability as well as, perhaps most obviously, their strategic location in the centre of major capital cities. Another crucial example is the Square Maximilien in Brussels, where the Plateforme Citoyenne de Soutien aux Réfugiés or BXL-Refugees launched a different approach to occupation by using the centrality of the square to serve as a point of contact to establish a network of beds that could be provided in individual homes. Yet we should be wary of insisting too much on this centrality for in many respects what is most significant about the ways in which these autonomous communities and occupations are transforming the landscape of political opposition across Europe, lies in the multiplicity of initiatives of this sort, characterised by variations in scale and duration, in modes of interaction and negotiation, but united by the common feature of bringing a discourse of solidarity to the fore in the expression of new territories of resistance or ‘zones à défendre’ (Subra, 2017; Barbe, 2016).

Strikes

The autonomous and unauthorised nature of the spaces and squats so far discussed, makes it impossible to record with any certainty the numbers of people who have found refuge and solidarity for longer or shorter periods in these sorts of informal environments. In the middle of 2017, the Athens authorities recognised that there were probably 2,500 to 3000 asylum seekers living in squats across the city while the waiting list for a space at City Plaza Hotel ran to 4000 names; and Notara 26 would later claim that over 6000 people had lived there for some period of time (Chrysopoulos, 2017). But if local authorities in all contexts across Europe attempt to minimise the phenomenon, many commentators know and this book clearly documents, that the informal or civil-society sector has filled a glaring gap in both NGO and government or UNHCR-led provision for asylum seekers in continental Europe (Mayblin and James, 2019; Brugère and Le Blanc, 2017). The key role borne by these organisations whose work is by definition uncounted and unrewarded, at least in monetary form, explains why some have used the threat and actual implementation of strike action to draw attention to what they denounce as the irresponsibility of national governments. Clearly the context of voluntarism, compounded by the fact that for many their commitment was prompted by the sense of absolute necessity, means that this traditional mode of resistance by withdrawing labour power is only a marginal occurrence, but still a very significant one for a what it means to think solidarity, and particularly transnational solidarity, through a political lens. It also reflects the way in which some of the initiatives that began in a surge of compassion and sense of urgency have now become part of a new landscape in which street breakfasts, camps, clothes distributions, outdoor language classes, have become ‘normal.’ Several years on from the outpouring of volunteers and donations that marked the summer of 2015 in the UK in particular, the crisis is still ongoing and the volunteer organisations have moved in different ways towards more stable configurations. Recourse to the weapon of strike action reflects this often punitive ‘stabilisation’ and it reveals a number of key facets of what we mean by the politics of refugee volunteerism. In light of it, this chapter will go on to consider what it tells us about the forms of self-rule at work within sites of anti-authoritarian solidarity politics and how these have endured the long-term of the ‘crisis’ (Blanchard and Rodier, 2016). It will then turn to the relations that have also emerged between these initially autonomous organisations and larger structures, such as major NGOs or the local city authorities, who have in some instances found new ways to come together in the face of the now embeddedness of ‘the refugee problem.’

Withdrawing labour is a classic form of collective action, relying on solidarity amongst those exposed to unfair practice or injustice. What conditions have to prevail in order to achieve this sort of solidarity and how does it relate to the expressions of solidarity with destitute refugees? A broad swathe of the main volunteer organisations active in Paris put the commonality of their cause to the test in April 2019 by calling for a one-day strike on all ‘informal’ food distributions in the capital. Although still unauthorised by the authorities and so constantly at risk of criminal proceedings being brought against them, the fifteen citizen groups who joined the strike, including international, national and local groups (Solidarité Migrants Wilson, Ptits Déjeuners Solidaires, Utopia 56, Emmaüs France, Médecins du monde), provide a vast amount of the front-line support in the French capital for victims of the asylum process in Europe. They estimated that each week more than 15,000 meals are provided on this basis, that over 1500 people receive a cover or a tent in which to sleep every week on the strength of donations and unpaid labour, while 600 people are housed by local people on a voluntary basis, which still leaves anywhere up to 1600 people in the streets in and around the city because of the inadequacies in processing claims for asylum. The director of the major NGO France Terre d’Asile, mandated by the French government to function as a first port-of-call for asylum seekers, expressed his support for the strike, saying that if the capacity to manage the pressure on the system is not rethought, the whole chain of engagement will continue to run behind the needs, until everyone is exhausted (Birchem, 2019). This strike echoes earlier action expressed in Calais back in the early summer of 2015, prior to the major mobilisation from the UK, when the Calais Ouverture and Humanité collective publicly withdrew its support and organisation. More recently, in May 2019 and again in the Calais area, Jean-Pierre Boutoille, known as the ‘curé des migrants’ or ‘priest of the migrants,’ called for a suspending of volunteer activity in order to provoke the authorities into responsible action. And in a context I will return to further on, it is also worth noting here that Utopia 56 and Doctors Without Borders took the decision to pull out of the work they were mandated to do on behalf of the Paris municipal authorities less than a year after the creation of the ‘one-stop’ Humanitarian Centre at La Chapelle in Paris. They were protesting against the conditions inflicted by this very centre, in particular through desperate management of the queue system, on people hoping to claim asylum in the French capital.

In all these cases, the target of the action has been the national government or the local authorities, situating this activism firmly within the classic political arena of welfare provision and rights within a nation state. This frame explains some of the difficulties and differences that characterised the initial arrival of large numbers of British volunteer organisations in Calais in 2015. Reviewing the impact of the British presence one year on, the local député or MP for the Calais area Yann Capet pointed in particular to what he perceived as the absence of any political understanding amongst the scores of people who had upped and taken the ferry to the French coast. ‘Why are they not campaigning with the British government who is equally responsible for this situation?’ he asked, revealing his own ignorance of British politics (Laurent, 2016). Evidently he was not taking account of the broad and significant mobilisation in the UK in a year when the campaign led particularly by Lord Alf Dubs, in concertation with the UK organisation Safe Passage, capitalised on increasing national awareness of the plight of unaccompanied minors stuck in Calais with a claim to travel to the UK. Tens of thousands of people marched to Downing Street under banners reading ‘Refugees Welcome Here’ in the autumn of 2016 when Capet was interviewed, and many of these people had already taken to the streets a year earlier, in September 2015, when the group Solidarity with Refugees spearheaded what would become a massive demonstration, channelling the major shift in consciousness prompted by the photo of Aylan Kurdi. With over 100,000 demonstrators, this march was the biggest expression of collective solidarity with refugees that the UK had ever seen. Prior to that, and as these pioneer organisations acknowledged, the frame of action had been much more grassroots and their small gains were hard-won. The Syria Solidarity Campaign is a case in point. They had been active since 2012, joining forces with the broader organisation Citizens UK to lobby local councils to get them to agree to house fifty refugees. In the wake of the autumn 2015, they extracted the pledge from Prime Minister David Cameron to welcome 20,000 Syrian refugees. The difference was extreme, though as we now know, this pledge that would never be honoured. Capet’s comments are, then, more a reflection of the relatively insular or national quality of mainstream media reporting, on both sides of the Channel. This insularity and its essentially ‘monolingual’ character, which establishes the tone of the national ‘conversation’ on immigration, is in sharp contrast with the complexity of experience amongst activist volunteers often working in multilingual environments and adapting to different cultural practices, both within and between groups of displaced people and the different European organisations.

Yet drawing a neat distinction between ‘mobile’ people and ‘fixated’ national media spheres is also problematic. For as this chapter argues, many of the citizen-led, self-rule organisations are deeply embedded within national and local political dynamics, unwilling to disconnect their actions from the frame of representational politics and their opposition to new national legislation or domestic regulations and policing practices, often operating at the local-authority level (Cantet, 2016). The effects of this intersection between the local, the national and the transnational were particularly complex in Calais, where the initial experiences of co-habitation between British and French groups were not easy. The Auberge des Migrants in particular, present in Calais since 2008 when the informal camps started to spread along the coast and into the scrubs after the Red Cross Sangatte Centre was closed partly at British request, was critical of what they perceived as disorganisation, with the sudden arrival of large numbers of people and initially somewhat chaotic distribution of donations, pointing to what looked to them to be a cavalier attitude on the part of groups with little experience of the complexity of the situations at play and less concern for the evolving ecology of the settlement that would become known across the world as ‘the Jungle’. This was a problem of solidarity in the eyes of the local activists, who feared a ‘drive and drop’ model of engagement that risked running counter a longer-term political response to the situation. In contrast, many UK activist volunteers were appalled by their impression of public indifference to the suffering in and around Calais. To some extent these differences still endure today and raise the question of what it would mean for this mass mobilisation across Europe to evolve towards the more structured form of a truly transnational ‘movement’. And the contrast with how things evolved between British and French groups in nearby Grande-Synthe, a suburb of Dunkirk, where the local Mayor took a much more progressive approach and called on a range of non-state actors, including both French and International organisations, also points to the determining effects of the local political context.

It is important to observe, then, that even within the UK ‘charity sector’ operating in and around Calais, significantly different approaches emerged as the situation evolved. Care4Calais, for example, has preserved a primarily British profile and sought to build connections with UK organisations such as the historic formation of Stand Up to Racism, and newer networks such as the very active STAR or Student Action for Refugees organisation, with whom Care4Calais coordinate mass volunteer visits to Calais several times a year. They have also extended their operations to developing a supply chain towards Syria, while on the home front they have been amongst the most prominent voices denouncing the massive funding by the British government of security at the UK border in Calais, drawing attention to British complicity in the nightly tear-gassing of ‘Jungle’ residents including children, the firing of rubber bullets, and the regular imprisonment of undocumented migrants. In contrast, Help Refugees which was initially the focus of the Auberge des Migrants irritation, has now built a partnership with that organisation, contributing significantly to swelling the collective budget. It flags up its engagement in research as well as day-to-day work, an approach it underscores in its self-description as adopting a ‘field-work first approach to aid, establishing local networks and working with local partners….’

These Calais examples show some of the difficulties not only in describing the mobilisation in 2015 as a collective political movement, but also in assessing the frame within which action is grasped as meaningful. When volunteers sprang into action in the face of what they saw happening in Calais, the time scale within which they placed their actions was quite radically at odds with those present since the early 2000s, and different again from those who as Priest Jean-Pierre Boutoille points out, have often spent years in forced displacement in Africa and the Middle East before they reach Europe. Throughout all these examples, we see clearly the inevitable tension between volunteers seeking to meet immediate mass-survival needs such as food, drinking water, or basic shelter, and the project of laying the groundwork for a new politics of solidarity. And many of the testimonies in this book speak to the frustration felt by those committed to short-term emergency aid when they also clearly grasp the need to engage with the political ramifications and implications of the ‘crisis’.

Resistance to a discourse of ‘crisis’ with its short-term implications explains a lot of what has prompted many refugee and undocumented-worker-led movements to insist on building a sustainable autonomous movement in which volunteer contributions from European citizens would be at most marginal. In many instances these groups remain fluid and invisible, or when visible, local and mobilised around specific demands for equal pay, access to health care or accommodation (Nyers 2015). There are exceptions, perhaps most notably the International Committee of Refugees initiated in the UK in 2015 and now based in Germany. This is one way in which the ‘long haul’ realities of global migration have redirected and absorbed the ‘uprising’ of solidarity at its height in 2015-16. In most instances, though it has resulted in relatively local and complexly transnational configurations where the project of building a politics of solidarity outside the frame of traditional forms of representation, is taken forward in incremental ways that have been referred to as ‘kinetic politics’ (Cantat, 2018). The focus for these movements is generally more on internal communication and less on high-visibility websites. The other way is through alliance with intermediary actors and most notably city authorities, whose position enables them to stand in opposition to national governments yet offer a stabilising platform, as well as recognition and resources for citizen activism. We will now turn to these two alternative horizons.

Self-Rule

There was perhaps no more charged distinction at play in the fraught sequence of 2015-2016 than the media trope of the asylum seeker versus the undocumented or irregular migrant. The sans-papiers (‘no papers’) movement, launched in the mid-1990s in France, had long decided that there was nothing to be gained in that debate and the only possible course of action was to reject the distinction by defining its own terms. These terms had to draw attention to the fact that the people in question had all the attributes of citizens – jobs, qualifications, families, tax returns, responsibilities – and what they lacked were the papers to circulate freely and potentially, in the longer term, to vote. They came to visibility at what can now be seen as a turning point moment, after the large numbers of Vietnamese and later Albanian refugees had found safe haven in France in particular, and before the major population movements from the Middle East and Africa of the first two decades of the twenty-first century. They were not claiming to have fled war, though many had lived under repressive regimes. They were in France, and had been for numerous years in many cases, for mixed reasons: some push factors, some pull factors. The legal framework prevailing on them had changed gradually through a series of reforms, reducing their rights and sometimes compromising their continued existence in the country where they had built a life, founded a family. They were campaigning for ‘régularisation,’ and they still are.

In 1996 they occupied the Saint Bernard church in Paris, drawing substantial media attention until they were evicted and some were put in detention. The occupation was the moment of self-declaration as an autonomous political movement. In 2008 they led another high-profile occupation, this time against the general workers union that had represented some of them. This second occupation was important for the way it focused solidarities. Though the CGT union had supported the claims to papers for some of its sans-papiersmembers, it refused to extend its support to isolated and often non-salaried workers, particularly women who earn their living doing ‘informal’ labour like cleaning. In opposition to this discrimination, the sans-papiersoccupied the union headquarters near the Place de la République. This choice was highly strategic and bears out what many commentators observe as the parting of ways between new forms of political protest and traditional representative mechanisms, such as unions. The actual location, much closer to the centre of the city than the Saint Bernard church, was also significant. Place de la République would later to be the site of the massive homage to the victims of the Charlie Hebdo attacks after the Kouachi brothers broke into the offices of the satirical newspaper in January 2015 in the name of an Islamist terrorist group and killed 12 members of the editorial team, injuring eleven more seriously in the process. The following year, the radical street-occupation known as Nuit Debout that grew out of opposition to new French labour legislation also centred its actions on this Place, prompting some efforts to create visibility for migrant camps in and around this period of revolt. While not achieving anything of the scale and visibility of the several-thousand-strong camps on the northern fringes of the city since 2015, these gatherings were still significant in this very visible and symbolic urban intersection.

This layering of political significance within one site, from ‘migrant politics’ to solidarity with a historic national newspaper, anchored on the Left though strongly criticised today for its incendiary representations of religious symbols, is important for, like in Exárcheia, it reveals how actions of refugee solidarity in spaces of long and dense political culture, such as Paris and Athens, draw from their antecedents while also transforming the landscape. Around the Place de la République during the sans papiers occupation, the walls were papered with large prints of photographs taken of two people holding one passport between them. The pairings blurred any easy categories, playing also with strategies of visibilisation. They were the result of spontaneous requests from individuals who presented themselves to be photographed with people in the occupation, inserting themselves into a story that was and wasn’t theirs. Since that time the sans papiers collective, known as CPS75, has continued to fight for rights to residency permits, while also bringing its long experience to bear in support of more recent groups mobilised in the name of newer generations of undocumented people. A number of the groups active today in Paris have direct connections with CSP75, and other organisations created to assist migrant workers recruited in the 1960s by French and European businesses now offer key legal support for people caught in the inequities of the ever more complex and punitive asylum system. A similar account could be given of the connections between the Plateforme Citoyenne du Soutien aux Réfugiés (BXL-Refugees) in Brussels mentioned earlier and the Belgium sans papiers collective, founded in 2009 after a series of failed efforts at regularisation, which has been particularly active in fighting the efforts in Belgium to pass a law allowing the police to enter individual homes to arrest ‘irregular’ migrants.

This longer history enables us to understand the significance of autonomous organisation and also its longer time-frame relative to actions prompted by a sense of urgency. And so we come back to the work of a group such as the BAAM, in order to underscore once more how that network has drawn from prior forms of politicisation of undocumented people to build a major refugee-centred support network that enables asylum seekers to transition from learners to become teachers, translators, coordinators. One such example within the BAAM group is that of Adam* from Sudan, who spent months in 2016-17 in a street camp near the Saint Bernard church that had been the rallying point for the sans papiers, surviving in permanent expectation of imminent deportation back to Italy under the Dublin regulation (Adam, 2017; see note 1 above). Through connections between the BAAM and the longstanding Association for Maghrebi Workers he learnt of the latter’s work, decided to volunteer as a translator from Arabic to English in the legal advice sessions they offer to enable communication with people arriving from Ethiopia and Eritrea. Attention to the necessity of translation in all situations of consequence for people in migration is one of the most frequently observed characteristics of movements led by those most directly exposed to repressive and violent border politics. This slow interface has prolonged and enriched the practice of direct democracy in many of the contexts described in this chapter. Regular assemblies during which collective decisions are lengthily debated and simultaneously translated are a feature of the squats and camps in Exárcheia as they are elsewhere. These practices are increasingly structuring academic work too, evident in the effort to ensure simultaneous translation during conferences and more generally to ‘decolonize multilingualism’ (Phipps, 2019). Similar practices and forceful attention to modes of interaction and protection of individuals are also at the heart of the methods of organisation developed by the Silent University, a truly international education platform initiated by the Dutch-based Turkish artist Ahmet Ögüt to foster ‘transversal pedagogies’ and obtain the recognition for refugees and asylum seekers with academic qualifications so that they can continue to do their work and research in Europe, in some cases despite death threats against them. It has established ‘decolonial universities’ in Sweden, Germany and Jordan and is currently developing a new location in Denmark, having begun through a collaboration in the UK with the Delfina Foundation and the Tate Museum. Though not at all premised on volunteer contributions, the Silent University, with its ambitious educational programme, has necessitated long and persistent negotiations with local actors, as well as the fostering of a strong internal community.[3] The emphasis on long-term commitment and full ‘buy-in’ to its principles and demands, as opposed to top-down direction or opportunistic gains, is fundamental to its approach. The internationalism of these facets of the mobilisation, built outside legal limitations and through fully participatory processes, is a protracted, highly complex, often contentious affair, frequently anchored in the idea ‘we live together, we fight together’. What we can hear in this expression is the effort to go beyond an opposition between the social and the political, forging new forms of political subjectivity in the joint objective of caring for people’s needs and building new forms of participatory organisation.

Local Authorities versus National Governments

The examples discussed here have focused on major cities and moreover on sites located within time-hallowed districts of these cities marked by histories of immigration and/or resistance to power. Accounts from these communities often invoke the significance of being in the centre. Proximity to shops, schools and services helps refugees negotiate a new environment while allowing them to blend into the diversity of a major urban area. But the practices of embedded solidarity and attention to the complex ecology of a community are perhaps more characteristic still of remote locations. The La Roya Citoyenne movement is a case in point. Best known for the lawsuits brought against Cédric Herrou for his actions in helping people cross the Italian-French frontier at Ventimiglia this valley has a long history of autonomous solidarity anchored in the movement of workers between Italy and France. It is also deeply engaged in new forms of ecology. The same could be said of the Plateau des Mille Vaches in the Auvergne mountains, another area of seasonal migrations and alternative ecology, or Riace in Italy, the target of more repression from Salvini and also another model of participatory development spurred by the arrival of African migrants in a remote and impoverished rural environment.

What distinguishes the central-city mobilisations in most European states from these smaller configurations is the political stakes for the local authorities in positioning themselves as actors in a cosmopolitan future in which cities thrive on diversity and constant transformation. This dynamic is very marked in Paris where the mayor Anne Hildago has waved the ‘refugees welcome’ flag in opposition to national government, pre-empting their responsibilities, yet also herself accountable for facilities and practices that ultimately abandoned vulnerable people to the streets and resulted in still endemic urban camps. For local activist volunteer groups, such as Utopia 56 which initially agreed to support the city’s humanitarian camp in November 2016, the experience has been harsh and the group’s distrust in the city’s will to address these desperate situations led them in 2019, as the summer holidays drew to a close, to install a camp including women and children in a highly visible public park. This overt ‘use’ of the camp as a political tool in the long wrangling with the authorities represents a new departure relative to the long-term determination of other organisations discussed here to establish independent and alternative modes of governance.

Other cities have managed to embrace the actions of volunteer solidarity more successfully and in turn amplify citizen resistance to the persecution and grievous neglect of refugees, whether on land or at sea. Perhaps the most prominent example of this is the City of Sanctuary movement, which has been widely acknowledged particularly in the UK as exemplifying hospitality and empowerment of asylum seekers. Several cities have distinguished themselves in this way since Sheffield launched the idea in 2007, but perhaps none more than Glasgow, which quickly became the city to house the largest number of asylum seekers in the UK after the dispersal policy was introduced in 2000. The focus of a large range of arts-based and social outreach initiatives has been to provide hope for a ‘desired future’, particularly during the long waiting periods when asylum claims are processed. To this end the Glasgow City Council has also developed substantial provision of internship possibilities and networks to enable refugees and their children to gain language, experience and confidence, with a view to enabling them to integrate more easily (Darling, 2010; Bagelman, 2013). A lot of these initiatives depend on citizen-engagement to run effectively, and many involved are acutely aware that they offer little interface with the protracted legal battles and uncertainties that are also part of everyday reality.

A more dissident model of city-versus-national government has also emerged more defiantly on the continent and particularly again in southern Europe. Italy has led the way with a number of dissident mayors against the positions taken by Salvini, as well as the ‘Tourists go home, refugees welcome’ message that has been affirmed by the city of Barcelona. Grande-Synthe, on the Channel coast, has also positioned itself in opposition to national and regional policy by working with non-aligned solidarity groups, and this has added momentum to the creation of the Migrations Alliance bringing together local authorities and civil sector organisations. This Alliance is significant for its inclusion of the Mayor of Sao Paulo and the explicit intention to draw on the dynamic launched by the 8th World Social Forum on Migrations in Mexico in 2018 and the 8thAfricities event in Morocco also in 2018. This new development, broadening the scope of this chapter towards non-European horizons in conclusion, reflects the growing ambition and scale of the new activist volunteer movements that have been the subject of this chapter. From often quite improvised and reactive beginnings we can see new patterns of political practice emerging. These practices often speak in many tongues and try out as many forms of participation as possible, thereby bringing into the political arena aspects of life that are traditionally assumed to be ‘merely’ domestic, such as questions of who cooks and what food is served, or who gets to speak in an assembly and in what language, and meanwhile who is caring for the children… In part, they draw their disruptive qualities from the fact that they often operate outside legal framework, and sometimes in overt contempt of law in the name of what has emerged more and more decisively as the key term of contemporary radicalism, namely solidarity.

In the summer of 2019 Carola Rackete, the German captain of the Sea Watch 3, an independent search-and-rescue ship sailing under a Dutch flag, docked in the port of Lampedusa without authorisation, risking the arrest and criminal investigations that ensued. This is just one particularly brave example among a myriad of actions that resist the hostile directives and discourse of an increasing number of nation states. Individuals have been prosecuted or harassed for the ‘crimes of solidarity’ of guiding desperate people over the border, or for serving food in the streets, or for offering a bed for the night. In all these cases the purported ‘illegality’ of the action within the frame of national law is countered by appeals to other sources of law, whether those be explicit codifications of human rights, maritime law, or declarations of principle such as the Palermo Charter mentioned at the beginning of this chapter as one sort of ‘inaugural’ moment in the complex drama this chapter has attempted to re-tell through a range of intersecting angles. These appeals reflect the emerging forms of new international citizenship, such as philosopher Michel Foucault defined it in 1981 during a press conference on the plight of the Vietnamese boat people:

‘There exists an international citizenship which as such has its rights

and duties, and which is obliged to stand up against all forms of abuse

of power, no matter who commits them, no matter who are their

victims. After all, we are all governed, and, by that fact, joined in

solidarity.’ (Foucault, 1994: 707-8)

It may not yet be clear what the most effective forms of this citizenship are, but the premises for its development are more and more manifest.

Anna-Louise Milne

References

Adam. (2017). ‘Yesterday I didn’t speak a word of French, today I am translating into that language’, Z, revue itinérante d’enquête et de critique sociale, n°11, pp. 28-30

Agier M (2011). Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government. Cambridge: Polity

Bagelman, J. (2013). ‘A Politics of Ease?’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 49-62

Barbe, Fr. (2016). ‘La « zone à défendre » de Notre-Dame-des-Landes ou l’habiter comme politique’, Norois, 238-239, pp. 109-130

Blanchard, E., et Cl Rodier. (2016). « Crise migratoire » : ce que cachent les mots », Plein droit, vol. 111, no. 4, pp. 3-6

Birchem, N. (2019). ‘A Paris, des associations en grève pour dénoncer la situation des migrants’, La Croix

Brugère, F. and G Le Blanc. (2017). La fin de l’hospitalité, L’Europe terre d’asile ? Paris, Flammarion

Cantat, C. (2016) ‘Rethinking Mobilities: Solidarity and Migrant Struggles Beyond Narratives of Crisis’, Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics, Special Issue, Vol.2

Cantat, C. (2018). ‘The Politics of refugee solidarity in Greece: Bordered identities and political mobilization’, Migsol Working Papers Series, 1

Chrysopoulos, P. (2017). ‘Number of Refugees Living in Athens Squats on the Rise’; Greek Reporter

Darling, J. (2010). ‘A city of sanctuary: the relational re-imagining of Sheffield’s asylum politics’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers I, New Series, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 125-140

Elias, A. J. and Ch. Moraru (2015). The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century, Evanston: Northwestern University Press

Fekete, L. (2018). ‘Migrants, borders and the criminalisation of solidarity in the EU’ Race & Class, Vol. 59 (4), pp. 65-83

Foucault, M. (1994) Dits et ecrits IV, Paris, Gallimard

Laurent, A. (2016). ‘Quand les Anglais migrent vers Calais’, L’Express

Le Blanc, N. (2017) ‘“Santé ! Et que la police se tienne loin de nous !”, Mouvements n°92, pp. 145-156

Malkki, L. (2015) The Need to Help: The Domestic Arts of International Humanitarianism, Durham: Duke University Press

Mayblin L. and Poppy James. (2019). ‘Asylum and Refugee Support in the UK: civil society filling the gaps?’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 45, pp. 375-394

McNevin, A. (2007) Irregular Migrants, Neoliberal Geographies and Spatial Frontiers of ‘The Political’ Review of International Studies, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 655-674

Orlando, L. (2015) International Human Mobility Charter of Palermo 2015 https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/ICP/IDM/2015_CMC/Session-IIIb/Orlando/PDF-CARTA-DI-PALERMO-Statement.pdf (consulted 1 Nov. 2019)

Paynter, E. (2018) ‘The Liminal Lives of Europe’s Transit Migrants’ Contexts, Vol. 17, Issue 2, pp. 40-45.

Phipps, A. (2019). Decolonising Multilingualism. Struggles to Decreate, Bristol: Multilingual Matters

Subra, Ph. (2017) ‘De Notre-Dame-des-Landes à Bure, la folle décennie des « zones à défendre » (2008-2017), Hérodote, n°165, pp. 11-30

Youlountas, Y. (2018). L’Amour et le révolution (film, Greek/French, prod. Berceau d’un autre monde)

[1] ‘Dublin’ is the colloquial term used across Europe to refer to the Dublin Regulation as described in the Overview chapter. In particular it dictates that a person must seek asylum in the first country of entry, which enables EU states to transfer asylum seekers to the first state in which their arrival in Europe was recorded, through fingerprinting, often in Southern Europe.

[2] This chapter is not concerned with delineating the distinctions between ‘migrants’, ‘asylum seekers’, ‘refugees’, ‘sans-papiers’: it is interested in situations which encompass these shifting and selective differentiations.

[3] One of the primary principles of the Silent University is full salaried pay even for academics living in illegality due to forced displacement. This commitment distinguishes it significantly from most of the organisations discussed here, but is nonetheless indicative of efforts to shift action away from the framework imposed by European differentiations between legality and illegality and towards new forms of alliance.